在-depth Q&A: What does the global shift in diets mean for climate change?

Josh Gabbatiss

09.15.20Josh Gabbatiss

15.09.2020 | 7:00amTo limit global warming while feeding an expanding population,every partof the food system from farming to refrigeration will likely need to become cleaner and more efficient.

At the same time, there isgrowing recognitionof the important role people’s diets will need to playin achievinginternational climate targets.

The food people eat is heavily influenced by culture, geography and wealth, but governments can also play a key role in influencing dietary change, through everything from farming subsidies to healthy eating guidelines.

在this Q&A, Carbon Brief examines how diets are already changing and what will be required to ensure the world’s food consumption is “climate-friendly”.

- What is a ‘climate-friendly’ diet?

- Why do people’s diets need to change?

- Are people in high-income nations eating more climate-friendly diets?

- How are diets changing around the world?

- When will the world reach ‘peak meat’?

- Can dietary guidelines help achieve climate targets?

- What else can governments do to alter diets?

What is a ‘climate-friendly’ diet?

There has been extensive discussion of what constitutes a “climate-friendly” diet. While there is no universally accepted answer and no internationally agreed guidelines, thescientific consensus聚集在少数关键特性。

Chief among these is the importance of keeping animal products – particularly red meat, such as beef, and dairy – to a minimum.

然而,肉类和奶制品的的影响climate is a complex and contentious issue, which is explored in far greater depth in Carbon Brief’s互动的讲解员.

- 在teractive: What is the climate impact of eating meat and dairy?

- Experts: How do diets need to change to meet climate targets

- Guest post: Coronavirus food waste comes with huge carbon footprint

- Guest post: Are low- and middle-income countries bound to eat more meat?

- Webinar: Do we need to stop eating meat and dairy to tackle climate change?

Other elementsof climate-friendly diets are a diverse array of minimally processed grains, tubers, fruits and vegetables, preferably varieties that are less likely to spoil and do not rely on energy-intensive transport, such as planes. (Although food transport is arelatively smallconsideration for overall emissions.)

This article will focus primarily on the consumption of red meat and dairy products, as these have been the main focus of efforts to curb dietary emissions.

It will also mainly address greenhouse gas emissions from food, while recognising that there are several – often, butnot alwaysaligned – issues at play when optimising diets, including health, adequate nutrition and other environmental impacts.

Why do people’s diets need to change?

Concerns about the impact ofmeat and dairyconsumption on the climate and the wider environment are not new.

However, over thepast decadethere has been a growing focus on sustainable diets that can feed the millions of people around the world who are malnourished or obese, while remaining withinplanetary limits.

Apaperpublished in 2007 stated that the emissions from meat “warrant the same scrutiny as do those from driving and flying”. Two years later, the influential British economistLord Sternsuggestedeating meat would, ultimately, become as unacceptable as drink driving.

Nevertheless, so far diets havenot been subjectto the kind of political attention that has driven action to decarbonise other high-emitting sectors.

Prof Tim Benton, who leads the energy, environment and resources programme atChatham House, tells Carbon Brief the climate-food link has been “given legs” by theIntergovernmental Panel on Climate Change(IPCC) setting out the climate benefits of dietary shifts.

The launch of the IPCC’sspecial reporton climate change and land in 2019made it clearthe goals of theParis Agreementrequire a focus on food systems, with much of the resultingnews coveragefocusing on the scientists’ references to dietary change.

Dr Hans-Otto Pörtner, a co-chair of one of the IPCC’s working groups,said at the timethey “don’t want to tell people what to eat…But it would indeed be beneficial, for both climate and human health, if people in many rich countries consumed less meat, and if politics would create appropriate incentives to that effect.”

There is already much discussion around efforts to create a “Paris-compliant” food system by reducing emissions per unit of food produced, as well as using “climate-smart agriculture” and “sustainable intensification” to feed a growing population.

However, as arecent letterby a group of medical professionals to the Lancet points out, dietary change has been relatively “neglected” in international climate politics.

An analysisin 2018 of existingnationally determined contributions(NDCs) found that, while 96 addressed agriculture and 88 mentioned food waste, none mentioned diets.

Arecent reportproduced by a group of organisations including theUN Environment Programme(UNEP)证实,没有国家气候计划交货plicitly discuss sustainable diets.

它的结论是,增加饮食和食物浪费NDCs could set a course for cutting emissions by an extra 12.5bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e) each year, 20% of the reductions needed to deliver on the Paris Agreement’s1.5C targetby 2050.

Meanwhile, without wealthier countriescurtailingtheir consumption of red meat and dairy products, in particular, it is likely they willexceed regional targetsand make the Paris Agreement targets of 1.5C or “well below” 2C warming harder to reach.

Onestudyfound that at current rates of emissions growth from the sector, livestock could take up 37% and 49% of the global emissions budget “allowable under the 2C and 1.5C target, respectively,” in 2030.

Failure to implement “animal to plant protein shifts” would make drastic changes from other sectors “far beyond what are planned or realistic” necessary, wroteDr Helen Harwatt, an environmental social scientist atHarvard Law School.

Dr Jonathan Doelman, a scientist working onintegrated assessment modelsat theNetherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, tells Carbon Brief that dietary change features “moreandmore” in pathways to Paris targets. “It’s getting harder and harder to get to 2C or 1.5C with normal measures,” he says.

One reason for this is that dietary change not only reduces emissions directly, but also means more land ismade availableas livestock pasture is freed up.

在many future scenarios, this sparing of land makes space for the mass rollout of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) and afforestation projects. Dietary changes could mean there is less risk tofood securityas these projects compete with agriculture.

Doelman describes such changes as a “win-win” as there is also less risk that emissions from food production will beoutsourcedto other countries:

“You are basically 100% sure it will help, whereas, indeed, if you just put more forests in the UK and don’t care about what happens to the food production you displace, you don’t know if it’s actually a net gain for the climate.”

Dr Paul Behrens, a researcher who focuses on the environmental impact of human consumption atLeiden University, tells Carbon Brief that dietary change also has many extra benefits:

“It may be possible to hit the Paris Agreement with some heroic assumptions on how you could use sequestration without dietary change, but you’re not going to address water scarcity, soil degradation, biodiversity loss and eutrophication.”

The release of theEAT-Lancet planetary health dietin 2019 – described as the “first attempt to set universal scientific targets for the food system” – marked a “watershed” moment, with a call for a reduction of more than 50% in global meat consumption.

The study, produced by 37 scientists, provokedconcernsfrom the food and agriculture industry, anda statementfrom the Italian government said its recommendations could “end up being nutritionally deficient and even dangerous”.

But the report’s authors areclearthat in their view reaching the Paris Agreement targets is “not possible” by just decarbonising the global energy system, stating:

“过渡到食品系统,可以提供东北gative emissions (i.e. function as a major carbon sink instead of a major carbon source) and protecting carbon sinks in natural ecosystems are both required to reach this goal.”

Are people in high-income nations eating more climate-friendly diets?

Globally, there is no doubt the consumption of high-emissions food products has increased substantially in recent decades.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations(FAO)datashows that production of milk has more than doubled and meat more than quadrupled over the past 60 years. Production of beef, the food withthe largestemissions footprint, has doubled.

What is more, analysis conducted by Chatham House shortly before the Paris Agreement in 2015 found that in Brazil, China, the UK and the US, public understanding of the link between diet and climate change was “very low”.

Despite this, there are suggestions that high-income nations, particularly in Europe, have started shifting towards more plant-based diets.

Quinoa salad bowl in healthy vegan restaurant. Vienna, Austria. Credit: Glenstar / Alamy Stock Photo.

This apparent trend has seen the French president backinga citizens’ callfor a 20% reduction in meat and dairy consumption, as well as Germany described ina reportby the US Department of Agriculture as leading a “vegalution” – vegan revolution – in Europe.

Thegrowth invegetarian eateries and plant-based alternatives appears to be matched by the public’s eagerness, with63% ofGermans,51% ofCanadians and50% ofBritish people trying or willing to reduce their meat consumption, according to various surveys.

Moreover, while health andanimal welfareare frequently cited as factors behind these choices, polling has also shown consumershighlighting the environmentas animportant factorin their decisions.

However,Laura Wellesleyfrom Chatham House says that while the landscape has changed since she started working on this topic before COP21 in Paris, the extent to which behavioural changes are actually taking place is “still unclear”.

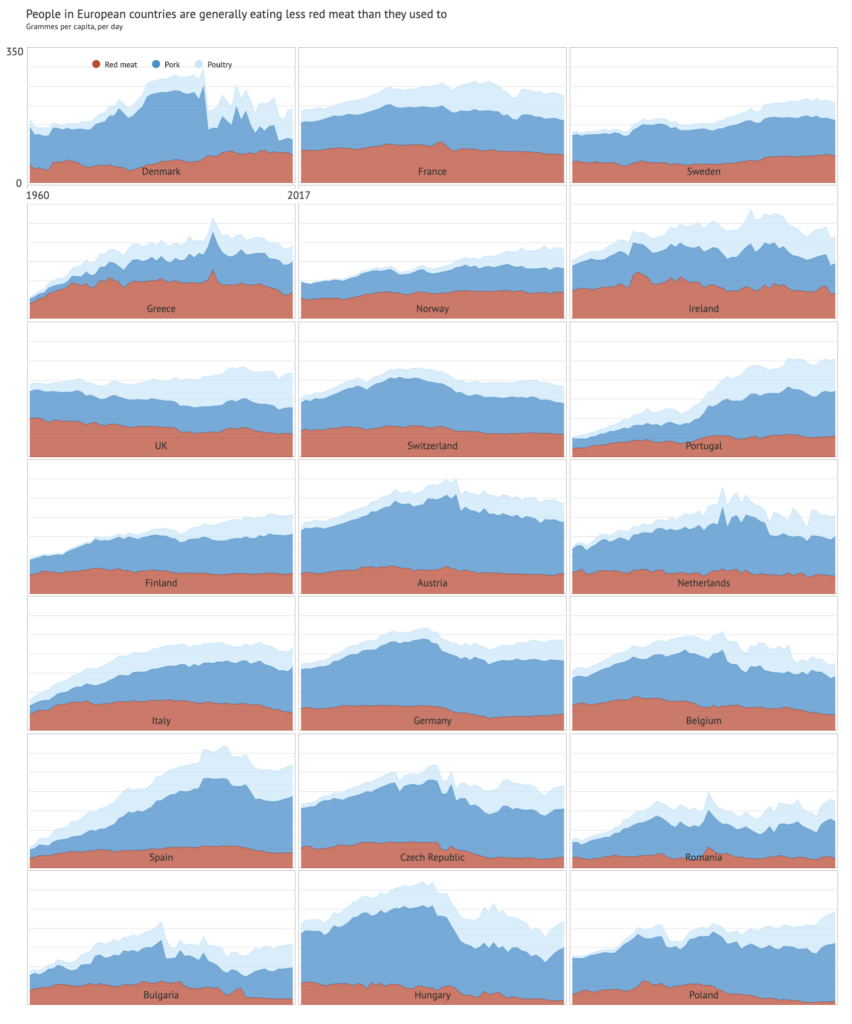

The chart below shows how per-capita meat consumption is changing across Europe, based onfood balance sheetdata from the FAO. Contrary to the idea of a shift to plant-based foods, overall meat consumption has seen a general increase, although most nations have experienceddeclinesin red meat intake.

Overall per-capita meat consumption is roughly twice the global average in Europe and dairy consumption is around three times higher, according to FAOdata. Meat consumption in Australia and the US iseven higher.

According to Benton, a key driver behind the decline in consumption of beef and lamb in some “western” countries is “red meat is bad” public health messaging that stretches back to the 1970s.

Meanwhile, high levels of meat consumption in nations such asSpainand Austria havebeen attributedin part to subsidised animal farming that results in cheap, easily available products.

Eastern European countries, including Romania and Bulgaria, see lower overall meat consumption, whichcan belinked to lower average incomes.

Dr Marco Springmann, a population health scientist at theOxford Martin Programme on the Future of Food告诉碳短暂,亚慱官网虽然有些富裕nations have shown a drop in per-capita red meat and dairy consumption, it is generally coming from a very high level.

The notion of a recent shift to vegetarianism and veganism is largely based on a combination of national diet data, consumer surveys and industry and retailer reports on plant-based foods.

However, Springmann says national dietary surveys have “huge problems”. Specifically, they are often based on self-reporting and there isevidencepeople in high-income nations under-report consumption, particularly for products they feel they should not be eating.

The UK government’s “family food” survey even includes the disclaimer: “It is a widely recognised characteristic of self-reported diary surveys…that survey respondents tend to under-report”.

“If people really ate only what is reported in the national dietary survey of the UK, everybody would be underweight by quite a bit,” says Springmann.

Meanwhile, the global “alternative meat” market was worth $14bn last year, according toresearchby Barclays, with particular interestamong young peoplefor dairy- and meat-free options.

This is just 1% of the global meat industry, although the same research predicted this could rise to 10% by 2029.

However, there is scepticism among experts. Wellesley tells Carbon Brief that in the UK the optimism of the “Greggs vegan sausage roll moment” should be treated with “a degree of caution”:

“We have had behind-the-scenes conversations with major retailers who have said that although meat alternatives sales have increased, so too have sales of conventional meat options.”

As the charts above indicate, declines in red meat tend to be made up for by an increase in pork and particularly poultry consumption.

While emissionsfrom theseproducts are far lower per gramme than red meat, there areconcernsabout some of the knock-on effects of their increased consumption, particularly due to their reliance on soy as an animal feed.

Soy production is amajor contributorto deforestation in South America. Pig and poultry farming in the UKconsume29% and 53%, respectively, of the solid “cake” derived from soy which is used to feed animals and, to a much lesser extent, humans.

Separately, areportby theEuropean Environment Agencyfound that, while the EU had seen a 14% overall decline in per-capita beef consumption from 2000-2013, the environmental benefits were “somewhat offset” by a 15% increase in consumption of cheese,another productthat comes with a considerable emissions footprint.

While red meat is still widely recognised as having the largest climate impact, some scientistsand NGOshave emphasised the need to address all animal products when targeting more climate-friendly diets.

“我个人的观点…是你真正需要的d to be doing is cutting your consumption across the board, of all kinds of animal products,”Dr Tara Garnett, leader of theFood Climate Research Networktells Carbon Brief.

How are diets changing around the world?

Garnett tells Carbon Brief that, in her view, globally, there is increasing awareness of the impact that land-use change, deforestation and livestock methane is having on the climate.

However, she notes that outside of “northern” nations, an appreciation of the role people’s individual diets play in driving climate change is “less clear” to her.

Dr James Benthamof theUniversity of Kent, who recently publisheda studybased on FAO data examining worldwide dietary trends, tells Carbon Brief there has been a “global convergence” in diets.

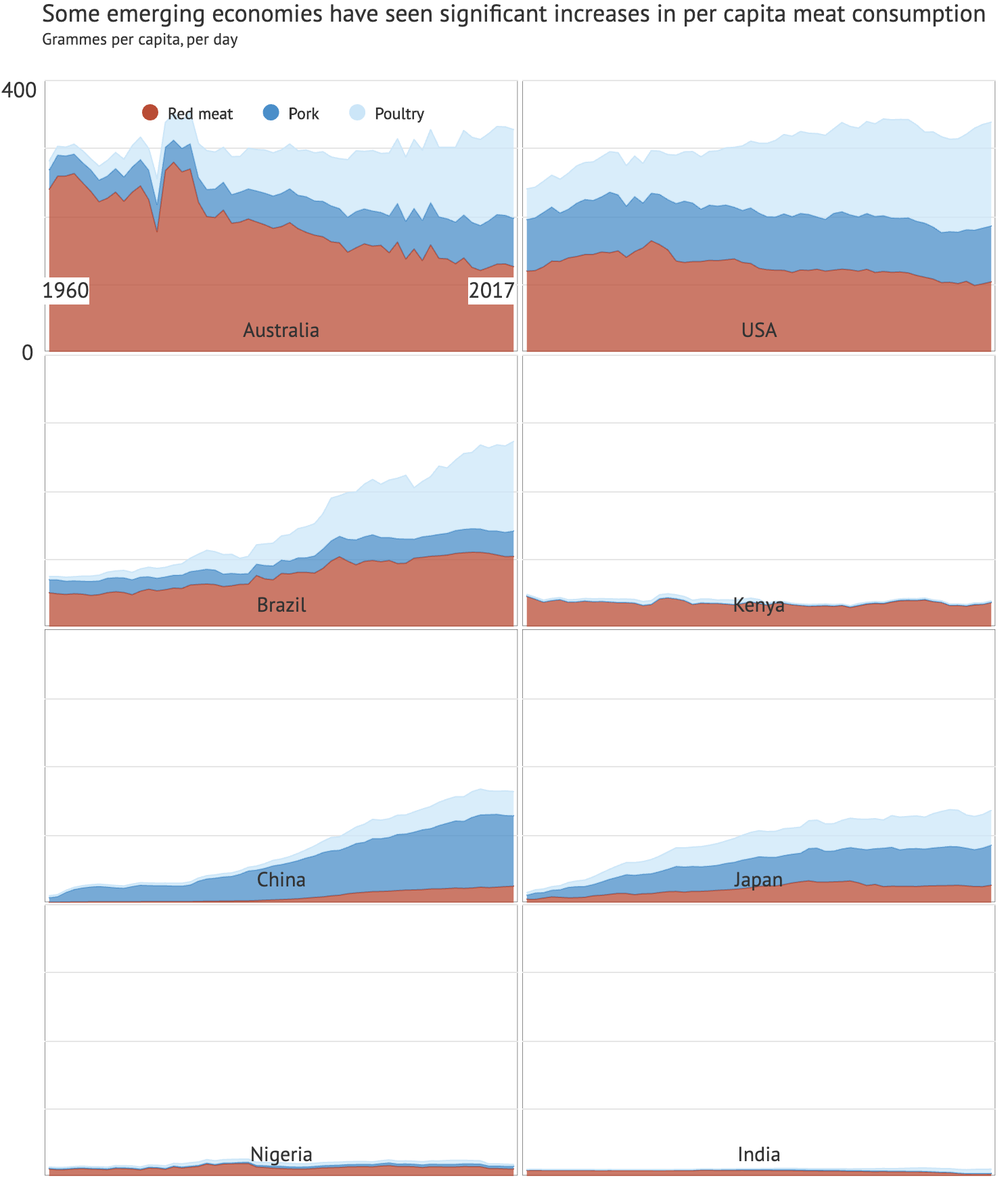

As people in western European nations, alongside countries such as the US, eat less red meat and dairy, inhabitants of emerging economies in Asia and South America tend to eat more of these products than they did in recent decades.

This trend can be seen in the chart below, based on FAO data for meat, with nations such as Brazil showing a significant increase in per-capita consumption while the US and Australia remain fairly steady.

Based on his analysis – which stretches from 1961 to 2013 – Bentham notes:

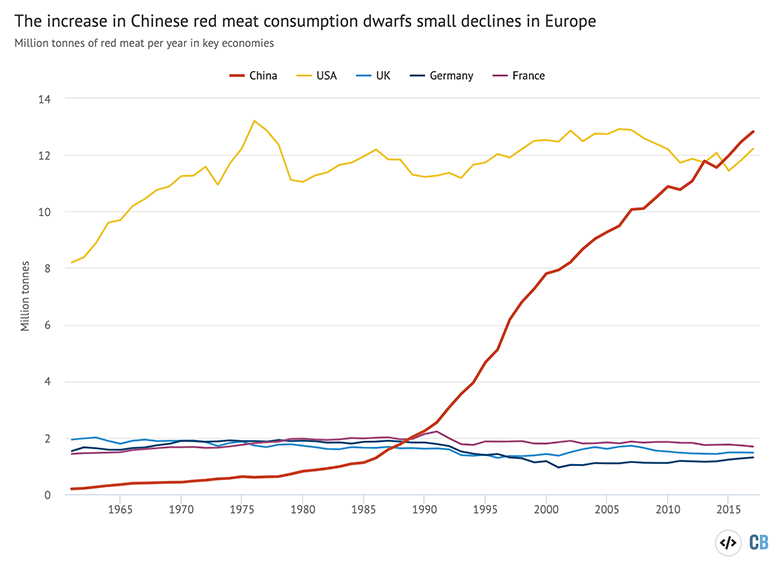

“The [per-capita] decrease in the west is not huge – and is not as large as the increase in China, South Korea and Japan, and then there’s just the fact that there are so many more people in East Asia than in the whole of the west.”

Meat and dairy consumptionhave beenconsiderably higher in Latin America than Africa and Asia for some time, with beef widely seen as a staple for the poor as well as the rich due to comparatively low production costs.

在Brazil, where the beef industry has aparticularly highenvironmental impact and farming is thelargest causeof national emissions,one studydescribed discussions in the country of the diet-climate link as “marginal”.

Meanwhile, for many people eating large amounts of meat is still not an option, as evidenced by the fairly low rates of consumption in African countries. However, growing populations alone are stillexpectedto result in nations such as Kenya and Nigeria significantly increasing their demand in the coming decades, even if per-capita intake remains low.

Researchers have noted that, when it comes to diets, there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach, arguing that many poorer nations will likely need to increase their dietary emissions to ensure their populations are eating healthily.

One recent study发现,在36个国家,约2.5基本脉冲电平lion people, the adoption of EAT-Lancet’s “planetary health” diet would increase agricultural emissions per capita by over 10%.

Dairyplays a big rolein this, as it is both emissions-intensive and alsorecognised asimportant for preventing stunted growth in children.

在a relationship that has been dubbed “Bennet’s law”,当人们变得富裕他们印康上升es tend tocorrelate wellwith rising meat and dairy consumption. Benton tells Carbon Brief:

“Eating meat for most societies around the world has been a high status activity…So there is quite a kind of anthropological determinism in that the more you develop from an economic perspective the more likely you are to eat more meat.”

However, Springmann notes this transition is not necessarily inevitable:

“As countries become richer, food industries become more interested in those countries, and they run heavy marketing campaigns to get people hooked on those cheap and processed food products.”

Benton agrees this trend is not “set in stone”, pointing to the example of在diaas a nation that, for various cultural, religious and economic reasons, has retained low levels of meat consumption. (It is, however, the world’slargest milk producerand its livestock sectoris responsiblefor more emissions than road transport.)

Devinder Sharma, a food and trade policy analyst, says that, while India is “blessed” with a largely plant-based food tradition, he attributes rising emissions from emerging economies to the imitation of both western diets and industrial farming practices. “The problem is mostly coming from western countries,” Sharma says.

“Gradually people are realising that a reduction in meat consumption is what is ideal for the world to survive…but that realisation is very slow,” he tells Carbon Brief.

Ultimately, the relatively small changes in western diets will likely not be sufficient from a climate perspective, especially if other nations continue increasing their consumption of meat.

This is, perhaps, especially true for China, where supporting meat productionhas beengovernment policy in recent decades and almosta thirdof the world’s meat is consumed. Much of the growth in global beef consumptionhas been drivenby China.

在2016, some English-speaking mediareportedthat the Chinese government’s new dietary guidelines aimed to reduce meat intake by half, in a move backed by celebrities and welcomed by campaigners.

However,Li ShuofromGreenpeace East Asiatells Carbon Brief that much of the hype is “unfortunately based on misleading interpretation of the policy”. He adds: “I did not observe any change that the guidelines created for the dinner table.”

When will the world reach ‘peak meat’?

Amid discussions around diets and climate change, the concept of “peak meat” has emerged, withspeculationaround when the world will arrive at such a point.

在a letter toLancet Planetary Healthlast year, scientists called for governments to “declare a timeframe for peak livestock” and incorporate this into their updated nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to the Paris Agreement.

They argue that, in wealthier nations, cutting demand for livestock products and not simply outsourcing production to other countries will be essential to create “Paris-compliant agriculture sectors”.

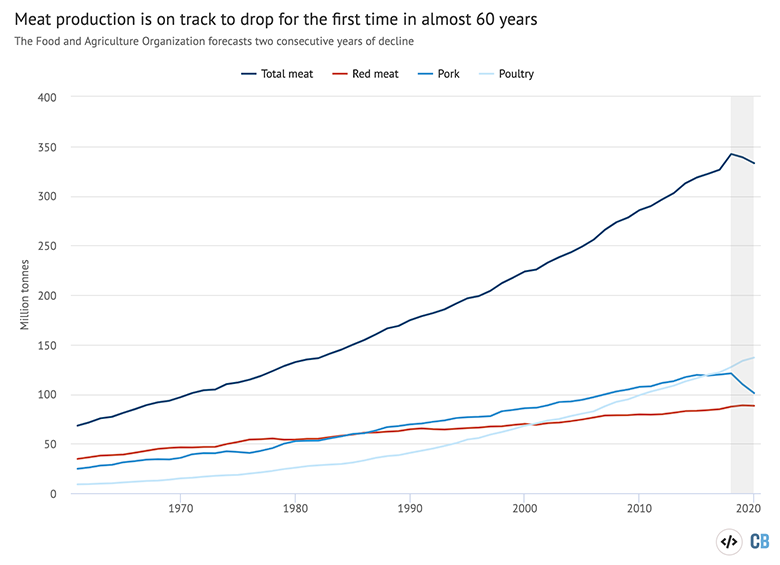

There is evidence that peak meat may be close.FAO forecastssuggest that in an unprecedented trend, after falling last year, meat production is once again on track to drop in 2020. Meat consumption per capita is projected to fall by nearly 3%.

While red meat production is set to decline slightly, with a 0.8% drop in beef, the main driver of this change is falling pork production, as the chart below indicates.

However, this projected decline comes in unusual circumstances. Meat production has been hit twice this year, first by theoutbreakof African swine fever which was already devastating pig farms in China and Vietnam and which has largely driven the fall in global pork output.

The other key event was the Covid-19 pandemic, whichhas disruptedall meat markets and supply chains due to labour shortages and facilities closing down temporarily.

The FAO did not specifically estimate the impact of coronavirus, but as the organisation’s chief economist Upali Galketi Aratchilage tells Carbon Brief:

“It is possible to think that meat production decline would have continued at the 2019 rate without the impact of the pandemic and that the pandemic aggravated it further.”

Demand for meat has also dropped alongside production, as reduced sales in the food service industry due to Covid-19 closures have only been partially offset by increases in retail sales.

Prior to the pandemic production of beef (the meat withthe largestenvironmental footprint) was already slowing down, even in nations such as the US andBrazil. On a per-capita basis, global beef consumptionpeakedin the 1970s.

While this seems like progress towards achieving overall peak meat, Aratchilage adds that prior to the pandemic they did not anticipate a global drop in demand for all meat products:

“Our data do not indicate such a fall at the global level, though consumption declines are observed in a few specific countries.”

Dr Helen Harwatt, who led the call for “peak livestock”, tells Carbon Brief signs of changing consumer habits are promising, but would not be enough to bring about the changes required:

“Not only do we need changes to happen on a much larger and more rapid timescale than what market signals from a relatively small group of consumers alone can deliver, we need system level changes to be implemented.”

Can dietary guidelines help achieve climate targets?

Given the slow progress away from high-emitting foods, experts haveconcludedthat interventions from official agencies and governments are likely to be necessary.

But despite the clear links between diets and climate change, fashioning policies in this area is still “politically toxic”, according toSimon Billingof the UK’sEating Better, a coalition of civil society organisations.

This point is echoed byJillian Semaan, who worked at the US Department of Agriculture during the Obama administration’scontroversial attemptsto encourage healthy eating in schools.

“Let’s be very honest, people do not like having their government tell them what to do,” she tells Carbon Brief:

带到s unsurprisingly, examples of targets being proposed by authorities to specifically reduce emissions from people’s diets are rare.

The EU’s recent “farm to fork” strategy indicated the importance of plant-based diets, but fell short of setting the targetsproposed by NGOs.

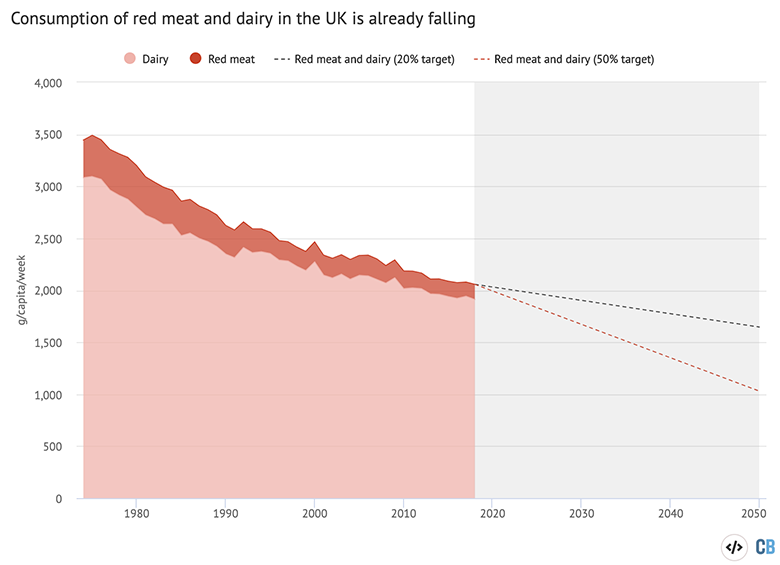

在its guidance onachieving net-zeroemissions by 2050, the UK government’sCommittee on Climate Change(CCC) recommends reducing consumption of “the most carbon intensive foods” – beef, lamb and dairy products – by 20%.

The CCC says this recommendation is in line with recent dietary trends in the UK, with the committee’s land analyst在dra Thillainathansaying this was chosen over another scenario in which red meat and dairy consumption was cut by a more ambitious 50%. (However, the 50% target still appears as part of the CCC’s “further ambition” scenario.)

The chart below shows that the CCC’s recommendations do indeed appear to be in line with trends in UK diets, based on self-reported surveying by the government.

Despite this, the CCC says current downward trends “are not likely to be sufficient” to deliver the required changes.

The UK government has accepted the CCC’s net-zero target, but it has been more ambivalent about the dietary guidance. In oneBBC Newsinterview, former climate minister Claire Perry described telling people to eat less meat as “the worst sort of nanny state ever”.

This attitude is not unique to the UK, with authorities in other nations, includingGermanyandIreland, showing hesitance in advising people to eat less carbon-intensive foods. Meanwhile, US vice president Mike Pencerecently accusedhis Democrat opponents of trying to “cut America’s meat” as part of their proposals for tackling climate change.

Billing tells Carbon Brief this is is partly to do with the fact that awareness among the public of the need for dietary changes to achieve climate targets is still fairly low:

“Politicians understand that I think and, therefore, they don’t like talking about it. We know in the climate community that it has to happen if…you’re going to get anywhere near net-zero.”

However, many governments already “tell people what to eat” vianational dietary guidelines. Manyresearchers, NGOsand theFAO itselfhave identified these guidelines as animportant opportunitytosubstantially reduceemissions.

As of 2016, anFAO reportfound just four countries –Germany,Brazil,SwedenandQatar– specifically referencing environmental concerns in their official dietary guidelines.Since then, more including Canada, Norway and Switzerland have joined the list.

Others, including the UK, France, the Netherlands and Estonia, had “quasi-official” guidelines produced by government-affiliated entities that mentioned the environment.

Meanwhile, attempts to incorporate such considerations into US and Australian guidelines havebeen shelvedafter opposition from the meat industry and farmers.

在stead, while dietary guidelines tend to vary depending on the culture they emerge from, health is generally seen as their priority. Fortunately, as Benton tells Carbon Brief:

“There is a commonality between what is a healthy diet and what is a low-footprint diet, primarily because the healthier diet is one that is richer in fruit and vegetables and lower in animal products.”

The CCC’s Thillainathan notes that the UK government’s healthy eating guidance, theEatWell Guide, recommends a much higher level of reduction than the CCC’s guidance, calling for an 82% cut from current levels of beef and lamb consumption.

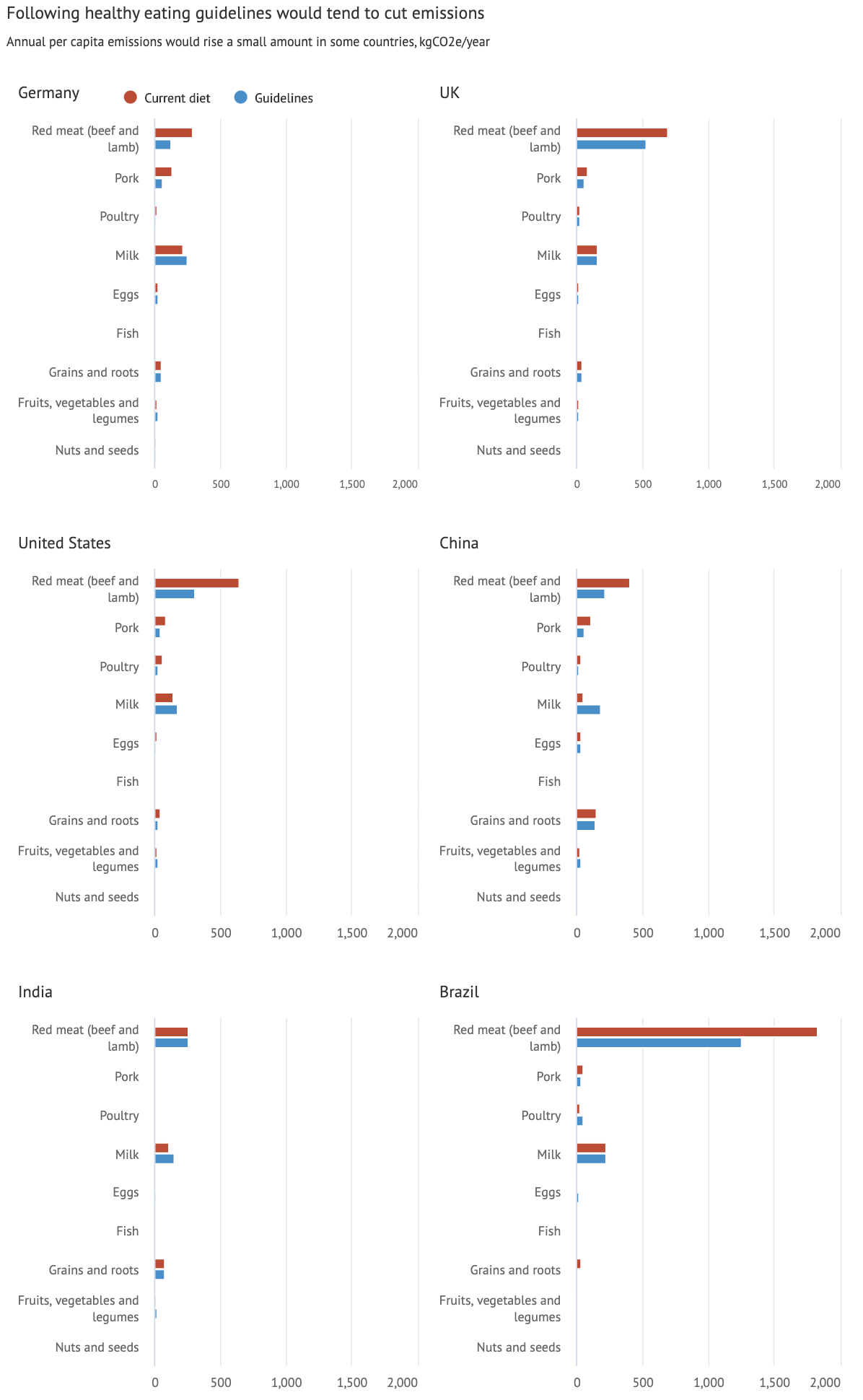

Arecent studyled by population health scientistDr Marco Springmann, found that the global implementation of dietary guidelines would cut food-related emissions on average by 13% – equating to 550MtCO2e – across all 85 nations with such guidelines.

Adoption of World Health Organisationdietary recommendationswould be associated with a similar reduction in emissions of 12% on average, the study found.

The impact that national guidelines could have on emissions, as well as the dominance of red meat and, to a lesser extent, dairy in the footprints of each nation, can be seen in the chart below. Often, following government guidance would result in dairy emissions rising.

Based on Springmann’s analysis, the blue columns show the total emissions per capita if everyone followed the guidance, compared to estimates of emissions from consumption in 2010, in red.

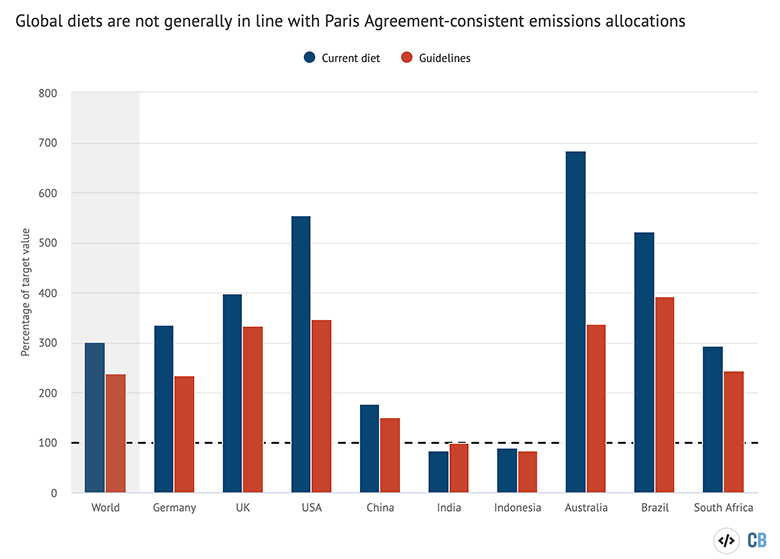

Crucially, while existing guidelines may cut emissions, they are far from being in line with the temperature rise targets set out in the Paris Agreement.

Dr Hannah Ritchieconducted asimilar analysisin 2018 and calculated per-capita emissions from food if everyone in a handful of major economies followed national dietary guidelines. She compared these figures to the global per-capita emissions required overall to achieve the Paris Agreement targets. She tells Carbon Brief:

“If we don’t see massive improvements in emissions factors [kgCO2e per unit of food production] or emissions from agriculture over time, by 2050 [food] would exceed the total economy-wide budget for 1.5C and not far off 2C, so there would be no room in the budget for anything else apart from food.”

Springmann and his colleagues came to a similar conclusion. For each country, they allocated a national emissions budget to food production under a pathway in line with 2C of warming. They then modelled full adoption of national dietary guidelines finding these, on average, to exceed the budget allocations by 140%.

Only 11 nations had dietary guidelines consistent with the 2C pathway.

The gap can be seen for a handful of key economies in the chart below, with the red bars indicating the emissions from guideline-adherent diets and the dotted line indicating the 2C-consistent allocation for food in 2050.

Finally, there is the problem of adherence. Not only are global nutritional and climate goals currently incompatible, but dietary guidelines are simplynot being followed, as Ritchie tells Carbon Brief:

“Some criticise the guidelines – that they are not going far enough – but the point is that we are still way off those guidelines.”

Springmann says that without policy support, providing information about food is not enough to encourage a meaningful shift in people’s diets:

“Just telling people not to eat this or eat that, doesn’t seem to work at all. Only if you implement that information and accompany it with actual policies that speak to that can it result in some difference.”

What else can governments do to alter diets?

Areviewin 2015 of efforts to shift consumption patterns away from meat, as well as other foods with high environmental impact, such as palm oil, found that such interventions were “extremely thin on the ground”.

Various stakeholders tell Carbon Brief this is still largely the case today, with many of the policies proposed by experts, including meat taxes and carbon labelling schemes, failing to find widespread support from policymakers.

A review of meat consumption trends inScienceconcluded: “The existence of major vested interests and centres of power makes the political economy of diet change highly challenging.”

Behrens agrees that beyond widespread unwillingness from politicians there are also many agricultural and industry groups that are “heavily invested” in the current system and unwilling to change.

However, while much of the progress in this area has been slow, Benton says the world could be on the cusp of a significant shift:

“If you think back to tackling other issues, such as smoking or Covid-19, you have a period where information grows and nothing happens, then suddenly something…causes a radical shift in opinions and then policy happens.”

To incentivise a “race to the top” in the food industry, the CCChas calledfor measures to increase the sector’s accountability and introduce monitoring and reporting standards for supply chain emissions.

Meanwhile, groups includingEating Betterin the UK and theGreen Protein Alliancein the Netherlands are advocating for changes to every aspect of the food system, which they say could influence people to take up more climate-friendly diets.

What follows is a selection of some of the policy instruments that have been proposed by scientists, NGOs and other stakeholders as key to driving substantial changes in global diets.

Taxes and subsidies

A carbon tax is viewed by many as a corecomponentof efforts to curb dietary emissions, by raising the cost of high-emissions food and discouraging people from buying it.

One studyconcluded that “optimal” taxation could cut emissions by 109MtCO2e, a reduction of 1.2% in food-related emissions globally, mostly due to reduced beef consumption.

Germany, Sweden and Denmark areamong nations讨论了“肉税”。投资者净workFarm Animal Investment Risk and Return(FAIRR)has saidsuch measures are “increasingly probable” due to Paris Agreement targets.

Dr Sinne Smedfrom theUniversity of Copenhagenhas conducted research into the impact of taxes on consumption, notably Denmark’s world-first “fat tax”, as well as thepotential benefitsof a carbon tax on food. She tells Carbon Brief:

“The idea of implementing a tax is that the prices should reflect the full cost of producing the food that you eat. If a food has high emissions then you should pay more because you pay the cost to the climate.”

Another studyfound that increasing the cost of beef by 40% and milk by 20% would be enough to account for their climate impact.

As with other taxes on foodstuffs, such as the UK’ssugar tax, the Danish tax on saturated fats faced significant opposition. It wasreversedafter less than two years.

Smed says that such proposals tend to face pushback in part because they are seen as being unfair to poorer people, who would no longer be able to afford certain foodstuffs.

However, to combat this researchershave proposeda system by which poorer households are offered rebates and revenues are used to fund programmes to promote plant-rich diets.

Other price-based mechanisms to change people’s diets include removing subsidies for livestock farming, which currently cost governments inthe EUandUSbillions every year, andsubsidisingplant-based alternatives instead.

A man browses US beef on a shelf at a discount store in Seoul, South Korea. Credit: Newscom / Alamy Stock Photo.

Public procurement

在2017, the German environment ministry facedcriticismwhen it announced it would only be serving vegetarian options at official functions.

Despite the backlash, “public procurement” measures are seen by many as a socially acceptable way to normalise the consumption of more plant-based meals with lower environmental footprints. Wellesley tells Carbon Brief:

“You might be able to change the food environment in schools, hospitals, government buildings and public buildings. As a means of creating new social norms, [that] is quite powerful.”

Sustainable procurement has seen some success in recent years, with various universities, schoolsand citiespledging to align their purchases with climate-friendly diets.

- 在teractive: How climate change could threaten the world’s traditional dishes

- 在teractive: How climate change shapes food insecurity across the world

- Meat and dairy consumption could mean a two-degree target is “off the table”

- Grass-fed beef will not help tackle climate change, report finds

- Farming overtakes deforestation and land use as a driver of climate change

在2017, Portugalapproveda law that ensures all public canteens provide vegan options, while recent legislationcould makeMaryland the first US state to set emissions reduction targets for food purchases.

According toUNEP, public procurement has “enormous purchasing power”, accounting for around 12% of GDP in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, and “up to 30% of GDP in many developing countries”.

Acknowledging there are “no silver bullets”, the UK’s CCC has suggested various ideas that could be implemented to encourage a dietary shift. Thillanaithan says the best place to start is probably with “low-regret, low-cost measures”, such as public procurement that cuts out meat and dairy products.

Behavioural ‘nudges’

Besides removing meat and dairy from public places, other behavioural “nudges” have been suggested as “low-regret, low-cost” ways to change diets that are relatively acceptable to the public.

Nudges include everything from reorganising products in supermarkets to adjusting meat portion size in cafes and restaurants.

TheBehavioural Insights Team, a former UK government unit, emphasised the importance of normalising sustainable diets in a report titled “a menu for change”:

“We enjoy eating meat and dairy in part because they are cheap…their consumption is normalised in our culture…they are heavily marketed; and nudged upon us…through myriad aspects of the choice environment in supermarkets and restaurants.”

This approach is given weight by the work ofAyse Allison, a PhD student atUniversity College London, who has studied the psychology of meat consumption. She tells Carbon Brief that one of her conclusions was that people eat meat simply “because it’s there”.

However,Professor Sir Charles Godfray, a population biologist and director of the Oxford Martin School, tells Carbon Brief he is concerned that governments might see nudges as “all they need to do”:

“If we are serious about [a] 1.5C or 2C world, we need to do much more than can conceivably be brought about by nudges and these subtle changes.”

He adds that while governments can “avoid headlines about it in the tabloid newspapers” by sticking to small interventions, they are “fooling themselves if they think that’s going to solve the problem”.

Education and carbon labelling

Education programmes and campaigns such as “meatless Mondays” have the potential to drive change, although it isdifficult to assesshow much impact they have.

在some nations, this might mean pushing back against the incursion of “western” food products. For example, Sharma says in India there have been considerable civil society efforts to promote the consumption of “core” national cereals, such as millets.

Japan isanother rare exampleof a nation that has had some success in limiting meat consumption despite economic growth, with the government promoting a traditional diet of fish, vegetables and rice partly in a bid to preserve self-sufficiency in food.

Carbon labelling is a form of awareness-raising that has been trialled extensively byfood companiesandsupermarkets, and, according toresearchby the Carbon Trust, is popular with the public.

Dr Pernilla Tidåkerfrom theSwedish University of Agricultural Sciences, who was involved in establishing awidely publicisedlabelling systemin Sweden in 2009, tells Carbon Brief accounting for exact emissions from each food product can be “difficult and costly”.

They opted instead for a “climate certification” scheme in which, for example, pork and dairy products are certified if they are from farms with emissions 15% below average.

While there is evidence that consumers find precise carbon footprints difficult to interpret,researchhas demonstrated that simple carbon labels do encourage people to choose low-emissions foods.

However,researchhas also indicated that for palm oil, a product that can be a major driver of land-use change and emissions in Southeast Asia, consumers still do not generally recognise sustainability labels, despite extensive campaigning by NGOs.

Language on labels could also have a big impact. One World Resources Institutestudyfound that changing labels from “meat-free” to “field-grown” increased sales by 17%.

Trade deals

On an international scale, trade flows could have a role to play in ensuring that the food people eat does not come with a significant emissions cost.

Garnett highlights trade as a “really important” influencer of global diets. She tells Carbon Brief that plans for the UK’s post-Brexit trade deal are a good example of this, particularly the extent to which “influxes of cheap, terrible meat from the US and places like that” are allowed in:

“That’s going to keep prices low and it’s going to either stimulate or at least maintain high levels of consumption.”

Producers of animal products in high-income countries “actively lobby their governments and trade ministers for improved access to new and emerging markets to support increased production and exports”, according torecent research.

Similarly, trade agreements to cut tariffs on agricultural goods have beenlinked torising meat consumption in the “global South”.

Professor Sir Charles Godfray was interviewed byDaisy Dunne.

-

在-depth Q&A: What does the global shift in diets mean for climate change?

-

在-depth Q&A: What the global shift in diets means for climate change