Guest post: How China and South Korea could save money by steering clear of gas

Warda Ajaz

08.02.22

Warda Ajaz

02.08.2022 | 8:00amChina and South Korea are planning to build more than 112 gigawatts (GW) of gas-fired power plants, making them the top two countries in East Asia, accounting for 80% of the region’s total.

These figures come from theGlobal Energy Monitorglobal gas plant tracker, which wasrecently updatedto cover more than 9,000 units, including nearly 700GW of new capacity under development around the world.

Yet international gas prices are currently atrecord levels, even as the cost competitiveness of renewablescontinues to improve. This presents an opportunity for the likes of China and South Korea, which could avoid a significant build out of gas and “leapfrog” to cheaper renewables.

According to the latest data from thinktankTransitionZero, the levelised cost of energy (LCOE) from renewables plus storage in South Korea and China is well below the cost of gas-fired power.

Both countries could take advantage of this current cost advantage to steer their power development plans toward more renewables.

Gas tracker

In 2020, Global Energy Monitor launched its Global Gas Plant Tracker, as a companion to the long-running coal plant equivalent. The tracker is designed to catalogue gas units with capacities of 50 megawatts (MW) or more (20MW or more in the European Union and the United Kingdom) and, following our latest update, it now contains more than 1,831GW of operational gas power capacity in 130 countries across the globe.

The tracker also covers another 692GW of new capacity under development, which includes gas plants that have been announced, have entered formal planning and are considered in pre-construction, or are in construction.

While the majority of existing gas power capacity is in North America, SE Asia and East Asia lead in terms of in-development capacity. Within the East Asia region, the vast majority of the 141GW of planned gas capacity is in two countries, namely China (93GW) and South Korea (20GW), as shown in the chart below.

![Capacity of gas power plants in development in East Asia, gigawatts, by country[/caption]](http://www.tjydzt.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Capacity-of-gas-power-plants-in-development-in-East-Asia-gigawatts-by-country.png)

At the same time, both countries have pledged to reach net-zero emissions by mid-century, withSouth Koreatargeting 2050 and China aiming for “carbon neutrality” by 2060.

Levelised costs

There have been significant shifts in the relative competitiveness of electricity from gas and renewables, as wind, solar and storage costs have continued theirdramatic declineand – in the past 12 months – as international gas prices havesoared.

Analysis from thinktankTransitionZerohas compared these alternatives on the basis of the levelised cost of energy (LCOE), which it defines as “the average total costs of building and operating a power plant, based on per unit of electricity generated over its assumed lifetime”.

For gas power, this represents the price per megawatt hour ($/MWh) at which project costs can be recovered and investors can achieve a minimum rate of return – known as the “hurdle rate” – on the capital and lifetime operational costs of the plant. This includes the fixed costs of building and maintaining the plant, as well as the short-run marginal cost of buying fuel and operating it.

For utility-scale solar or onshore wind with storage, LCOE is the price ($/MWh) needed to recover project costs and attain a required hurdle rate on investment. The methodology assumes a battery with half the capacity of the paired renewable source, capable of discharging for four hours. For example, a 10 megawatt (MW) solar site would have a 5MW battery holding 20MWh.

(Thedetailed methodologyfrom TransitionZero is available online.)

The analysis shows that in South Korea, the LCOE of solar plus storage is currently $120/MWh (red line in the figure below), as compared to $134/MWh for gas (black line).

![Levelised cost of energy from renewables plus storage and from gas in South Korea[/caption]](http://www.tjydzt.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Levelised-cost-of-energy-from-renewables-plus-storage-and-from-gas-in-South-Korea.png)

Along with its more than 19GW of planned new gas capacity, South Korea hasaround 20GWof wind and solar capacity already in operation, which together generated 5% of its total electricitygenerationin 2021. This is well below theglobal averageof 10%, as well as below other major Asian countries such as India (8%) and Japan (10%).

China has seenrapid growth采用可再生能源。2021年,在此y produced 12% of its electricity from wind and solar and this is due to reachnearly 20%in 2025.

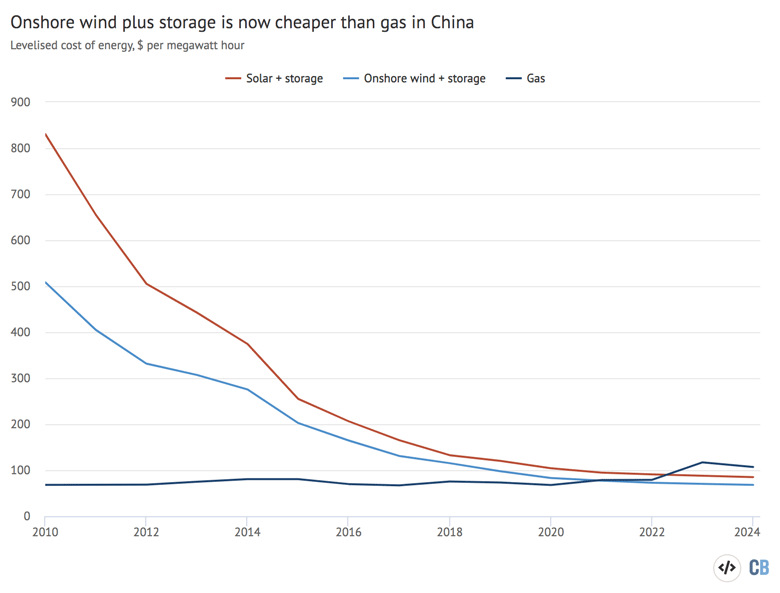

对中国来说,TransitionZero分析表明yabo亚博体育app下载onshore wind with storage currently costs $73/MWh, compared with $79/MWh for gas. Its figures suggest solar with storage will also become cheaper than gas by next year, as the chart below shows.

Development plans

With renewables plus storage now cheaper than gas, South Korea and China have a cost-effective moment to revisit their power development plans.

Investing in renewables instead of gas would not only save both countries money, but would also minimise the risk of being locked in to gas infrastructure commitments for a long period of time.

Moreover, the global fossil fuel market is at present highly volatile and subject to extreme price variation due to accidents, weather events and geopolitical shifts that can ripple around the world.

For example, the recent explosion at one of the world’s largest suppliers of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in Freeport, Texas, resulted in a4% increasein futures prices for LNG in East Asia. And a Julyheatwavein Japan pushed up power demand and LNG prices, as utilities sought extra fuel.

Geopolitical conflicts also have a bearing on the supply and price of fossil fuels, with the ongoing conflict in Ukraineillustrating clearlyhow the trade in energy can be “weaponised”.

相比之下,激起了enous renewables can ensure stable energy prices that are far less exposed to – even ifnot entirely immunefrom – the vagaries of geopolitics.

Finally, there is also an opportunity cost. If South Korea and China continue investing in gas, they may have fewer resources to invest in the renewables they need to meet their climate targets.

-

Guest post: How China and South Korea could save money by steering clear of gas