Factcheck: What is the carbon footprint of streaming video on Netflix?

George Kamiya

02.25.20

George Kamiya

25.02.2020 | 1:08pmThe use of streaming video is growing exponentially around the world. These services are associated with energy use and carbon emissions from devices, network infrastructure and data centres.

然而,与最近的一系列误导媒体coverage, the climate impacts of streaming video remain relatively modest, particularly compared to other activities and sectors.

Drawing on analysis at theInternational Energy Agency(IEA) and other credible sources, we expose the flawed assumptions in one widely reported estimate of the emissions from watching 30 minutes of Netflix. These exaggerate the actual climate impact by up to 90-times.

The relatively low climate impact of streaming video today is thanks to rapid improvements in the energy efficiency of data centres, networks and devices. But slowing efficiency gains, rebound effects and new demands from emerging technologies, includingartificial intelligence(AI) andblockchain, raise increasing concerns about the overall environmental impacts of the sector over the coming decades.

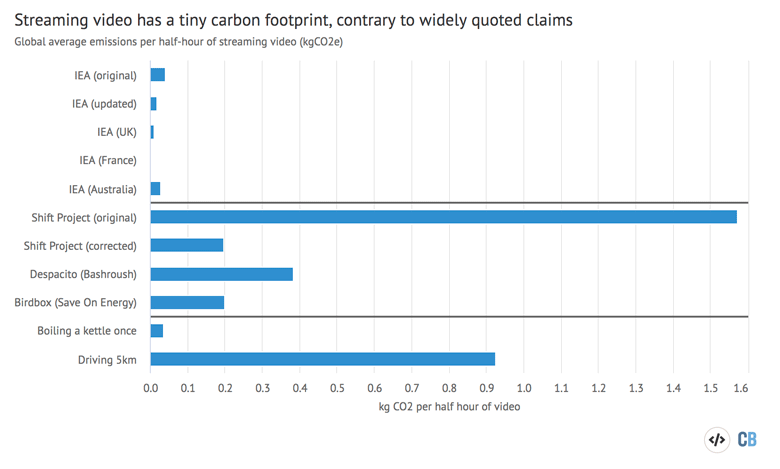

Update 25/11/2020:The energy intensity figures for data centres and data transmission networks have been updated to reflect more recent data and research. As a result, the central IEA estimate for one hour of streaming video in 2019 is now 36gCO2, down from 82gCO2 in the original analysis published in February 2020. The updated charts and comparisons also include the corrected values published by The Shift Project in June 2020, as well as other recent estimates quoted by the media.

Misleading media

A number of recent media articles, including in theNew York Post,CBC,Yahoo,DW,Gizmodo,Phys.organdBigThink, have repeated a claim that “the emissions generated by watching 30 minutes of Netflix [1.6 kg of CO2] is the same as driving almost 4 miles”.

The figures come from aJuly 2019 reportby theShift Project, a French thinktank, on the “unsustainable and growing impact” of online video. The report said streaming was responsible for more than 300m tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) in 2018, equivalent toemissions from France. The Shift Projectpublished a follow-up articlein June 2020 to correct a bit/byte conversion error, revising the original “1.6kg per half hour” quote downwards by 8-fold to 0.2kg per half hour.

The Shift Project’s original “3.2kgCO2 per hour” estimate is around eight times higher than a2014 peer-reviewed studyon the energy and emissions impacts of streaming video, while their “corrected” estimate of 0.4kgCO2 per hour is similar to the 2014 peer-reviewed study.

That 2014 study found streaming in the US in 2011 emitted 0.42kgCO2e per hour on a lifecycle basis, including “embodied” emissions from manufacture and disposal of infrastructure and devices. Emissions from operations – comparable in scope to the Shift Project analysis – accounted for only 0.36kgCO2e per hour.

However, because the energy efficiency of data centres andnetworks is improving rapidly–doubling every couple of years– energy use and emissions from streaming today should be substantially lower.

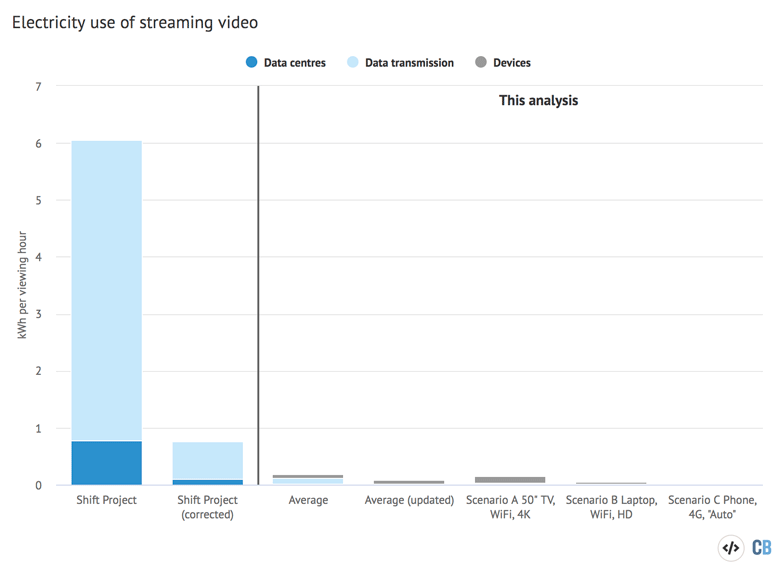

Looking at electricity consumption alone, the original Shift Project figures imply that one hour of Netflix consumes 6.1 kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity. This is enough to drive a Tesla Model Smore than 30km, power an LED lightbulb constantly for a month, orboil a kettle once a dayfor nearly three months. The corrected figures imply that one hour of Netflix consumes 0.8 kWh.

With167 million Netflix subscriberswatching anaverage of two hours per day,corrected Shift Project figures imply that Netflix streaming consumes around 94 terawatt hours (TWh) per year, which is 200-times larger than figures reported by Netflix (0.45TWh in 2019).

Another recent claim onChannel 4 Dispatchesestimated that 7bn YouTube views of a 2017 hit song – “Despacito”, by Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee, featuring Justin Beiber – had consumed900 gigawatt hours (GWh) of electricity, or 1.66 kWh per viewing hour. At this rate, YouTube – withmore than one billion viewing hours a day– would consume more than 600 TWh a year (2.5% of global electricity use), which would be more than the electricity used globally by all data centres (~200 TWh) and data transmission networks (~250 TWh).

It is clear that these figures are too high – but by how much?

Flawed assumptions

Theassumptionsbehind the Shift Project analysis (largely based on a2015 paper, whose assumptions have been significantly revised in2019and2020) contain a series of flaws, which, taken together, seriously exaggerate the electricity consumed by streaming video.

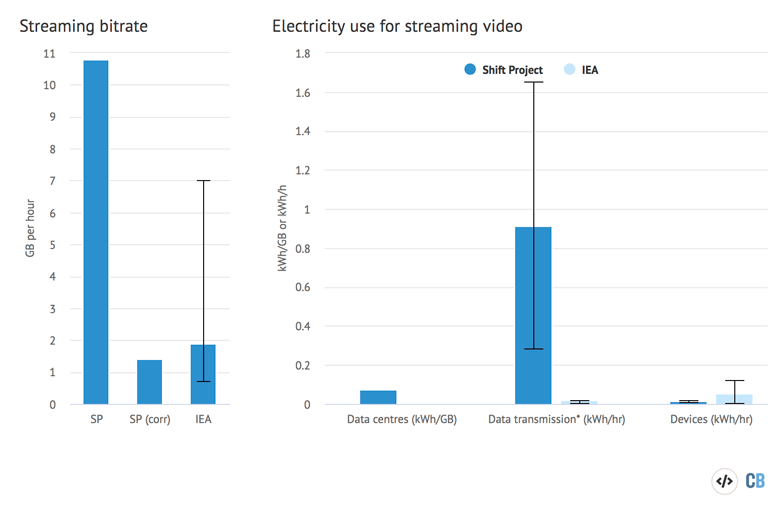

The original “1.6kg per half hour” claim overestimated bitrate, the amount of data transferred each second during streaming, apparently assuming a figure of 24 megabits per second (Mbps), equivalent to 10.8 gigabytes (GB) per hour. This was six times higher than theglobal average bitrate for Netflix in 2019(around 4.1 Mbps or 1.9 GB/hr,excluding cellular networks) and more than triple the transfer rate ofhigh-definition(HD, 3 GB/hr). Other typical transfer rates are 7 GB/hr forultra-high definition (UHD/4K), 0.7 GB/hr forstandard definition (SD), and0.25 GB/hr for mobile.

This difference stemmed from a stated assumption of 3Mbps apparently being converted in error to 3 megabytes per second, MBps, with each byte equivalent to eight bits. The Shift Project corrected this error in itsJune 2020 update, but did not revise any of its other assumptions, discussed below.

The chart below shows each of three ways that the Shift Project overestimated electricity use for streaming video – such as the bitrate – and one area where it underestimated the actual figure. These other errors are described in the text below the chart.

第二,转变项目分析高估了tyabo亚博体育app下载he energy intensity of data centres andcontent delivery networks (CDN)that serve streaming video to consumers by around 35-fold, relative to figures derived from2019 Netflix electricity consumption dataandsubscriberusage data.

Third, my updated analysis shows the Shift Project overestimates the energy intensity of data transmission networks by around 50-fold, based on average bitrates for streaming video. This is the result of using high and outdated energy-use assumptions for various access modes – for example, 0.9 kWh/GB for “mobile” compared tomore recent peer-reviewed estimatesof 0.1-0.2 kWh/GB for 4G mobile in 2019.

我原来的分析表明,2020年2月yabo亚博体育app下载Shift Project assumptions for data transmission energy intensity (0.15-0.88 kWh/GB) were much higher than more recent estimates (0.025-0.23kWh/GB). However, thelatest researchshows that thesedata-basedintensity values (kWh/GB) arenot appropriatefor estimating the network energy use of high bitrate applications, such as streaming video. Instead,experts adviseusingtime-basedenergy intensity values (kWh per viewing hour). Therefore, my assumptions for data transmission energy use have been updated withtime-basedenergy intensity values.

However, the Shift Projectunderestimatesthe energy consumption of devices by around 4-fold, because it assumes that viewing occurs only on smartphones (50%) and laptops (50%).According to Netflix, however, 70% of viewing occurs on TVs, which are much more energy-intensive than laptops (15% of viewing), tablets (10%), and smartphones (5%).

综上所述,我的分析表明,更新yabo亚博体育app下载streaming a Netflix video in 2019 typically consumed around 0.077kWh of electricity per hour, some 80-times less than the original estimate by the Shift Project (6.1 kWh) and 10-times less than the corrected estimate (0.78kWh), as shown in the chart, below left. The results are highly sensitive to the choice of viewing device, type of network connection and resolution, as shown in the chart, below right.

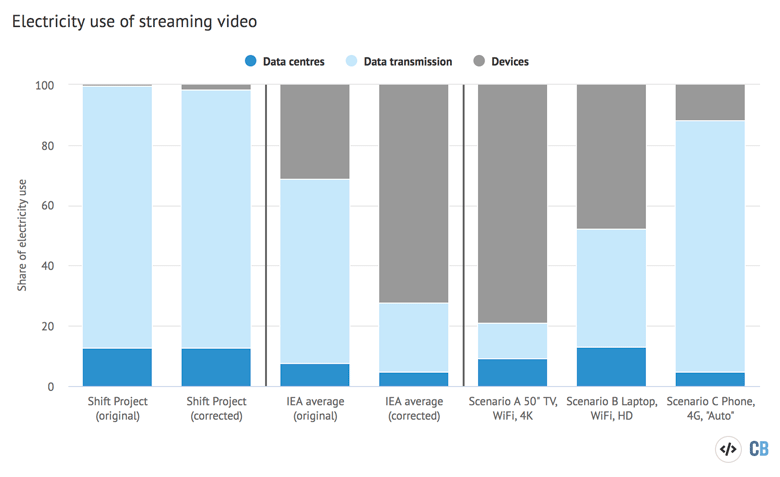

For example, a 50-inch LED television consumes much more electricity than a smartphone (100 times) or laptop (5 times). Because phones are extremely energy efficient, data transmission accounts for more than 80% of the electricity consumption when streaming.

Based on average viewing habits, my updated analysis shows that viewing devices account for the majority of energy use (72%), followed by data transmission (23%) and data centres (5%). In contrast, the Shift Project values show that devices account for less than 2% of total energy use, as a result of underestimating the energy use of devices (4x) while substantially overestimating the energy use of data centres (35x) and data transmission (50x).

Modest footprint

The carbon footprint of streaming video depends first on the electricity usage, set out above, and then on the CO2 emissions associated with each unit of electricity generation.

As with other electricity end-uses, such aselectric vehicles, this means that the overall footprint of streaming video depends most heavily on电是如何生成的.

Powered by theglobal average electricity mix, streaming a 30-minute show on Netflix in 2019 released around 0.018kgCO2e (18 grammes, fourth column in the chart, below). This is around 90-times less than the original 1.6kg figure from the Shift Project (leftmost column) and 11-times less than the “corrected” figure of 0.2kg (second column). The IEA estimate is also substantially lower than other estimates quoted in the media, including 22-times lower than theDespacito claim(cited onChannel 4,英国广播公司,FortuneandAl Jazeera, assuming a global average grid mix) and 11-times lower than theclaim by Save On Energythat 80 million views of Birdbox emitted 66ktCO2 (cited in theNew Yorker,Euronews,Forbes,Die Weltand theDaily Mail). My estimate of 36gCO2 per hour is more than 2,100-times lower thanMarks et al. (2020)who estimated that 35 hours of HD video emits 2.68tCO2, or 77kgCO2 per hour.

To put it in context, my updated estimate for the average carbon footprint of a half-hour Netflix show is equivalent to driving around 100 metres in a conventional car.

But as the chart above shows, this figure depends heavily on the generation mix of the country in question. In France, wherearound 90% of electricity comes from low-carbon sources,emissions would be around 2gCO2e, equivalent to 10 metres of driving.

Using country average emission factors may still overestimate emissions, particularly from data centres. Technology firms operating large data centres are leaders in corporate procurement of clean energy, accounting for abouthalf of renewable power purchase agreementsin recent years.

The electricity mix is also rapidly decarbonising in many parts of the world. For instance, the emissions intensity of electricity in the UKfell by nearly 60% between 2008 and 2018. Compared to2019 levels, global emissions intensity of electricityfallsby around a quarter by 2030 in the IEAStated Policies Scenarioand by half in theSustainable Development Scenario.

Digital efficiency

Although the carbon footprint of streaming video remains relatively modest, it might still seem reasonable to expect the overall impact to rise, given exponential increases in usage.

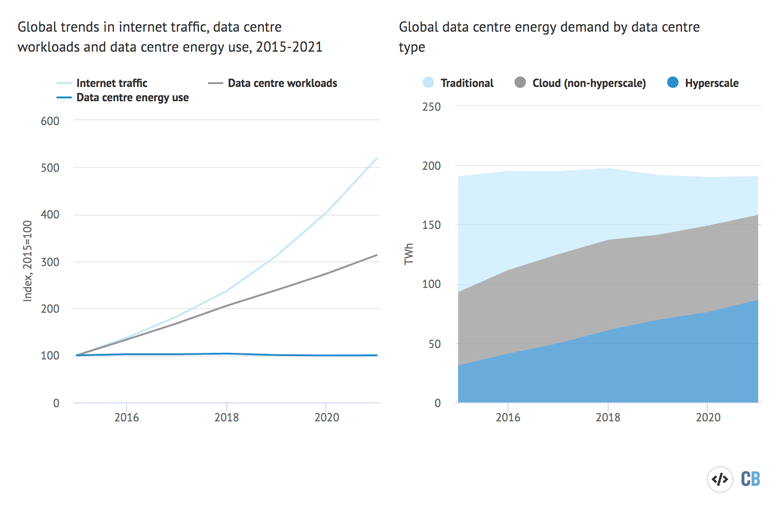

However, there have already been major improvements in the efficiency of computing, described by “Koomey’s Law”. This law describes trends in the energy efficiency of computing, which has doubled roughly every 1.6 years since the 1940s – andevery 2.7 years since 2000. A similar trend has been observed in data transmission networks, withenergy intensity halving every two years since 2000.

Coupled with the short lifespans of devices and equipment, which hastens turnover, the efficiency of the overall stock of devices, data centres and networks is improving rapidly.

For example, increasingly efficient IT hardware (following Koomey’s Law) and a major shift to “hyperscale” data centres have helped to keep electricity demand flat since 2015 (chart, below right). Data centres worldwide today consume around1% of global electricity use, even whileinternet traffic has tripledsince 2015 and data centre “workloads” – a measure of service demand – have more than doubled (chart, below left).

As well as changes that are invisible to the consumer, there are also obvious trends in the technology seen everyday. Devices are alsobecomingsmallerandmore efficient, for example, in shifts fromCRTtoLCDscreens, and from personal computers to tablets and smartphones.

Rising demand

Set against all this is the fact that consumption of streaming media is growing rapidly. Netflix subscriptionsgrew 20% last year to 167m, whileelectricity consumption rose 84%.

Manynew video streamingandcloud gamingservices have also launched in recent months. Particularly noteworthy is the rapid growth in video traffic over mobile networks, which isgrowing at 55% per year. Phones and tablets already account formore than 70%of thebillion hours of YouTube streamed every day.

The ease of accessing streaming media is leading to a largerebound effect, with overall streaming video consumption rising rapidly. But thecomplexity of direct and indirect effects of digital services, such as streaming video, e-books, and online shopping, make it immensely challenging to quantify the net environmental impacts, relative to alternative forms of consumption.

Moreover, emerging digital technologies, such asmachine learning,blockchain,5G, andvirtual reality, are likely to further accelerate demand for data centre and network services. Researchers have started to study the potentialenergy and emissionsimpacts of these technologies, includingblockchainandmachine learning.

It is becoming increasingly likely that efficiency gains of current technologiesmay be unabletokeep pacewith this growing data demand. To reduce the risk of rising energy use and emissions, investments in RD&D for efficient next-generation computing and communications technologies are needed, alongside continued efforts todecarbonise the electricity supply.

Broader context

Streaming video is a fairly low-emitting activity, especially compared to driving to a cinema, for instance. As consumers, we can further reduce our environmental footprint by using smaller devices and screens, which consume less electricity. Replacing devices less often can also help, since the production phase accounts foraround 80%of the lifecycle carbon emissions of mobile devices (andabout a third for televisions), andelectronic wasteis a growing problem across the world.

Much less data-intensive digital activities, such as email, have also drawn significant and misleading media attention regarding their carbon footprint. Recent headlines in theFinancial Times,GuardianandBloomberg Greenhave suggested that cutting back on e-mails could lead to substantial emission reductions –more than 16,000 tonnes per yearin the UK, if every adult sent one less unnecessary e-mail per day. These claims are based onanalysis by OVO Energywhich assumes that one unnecessary email emits 1gCO2, which come fromback-of-the-envelope calculations from 10 years ago. In reality, emissions from emails today are much lower, and experts haveexplained how and why these headlines vastly overestimate the potential emission reductions from avoided emails.

Technology companies can continue to play a big role in reducing the environmental impact of streaming, including through further efforts to increase energy efficiency – both in the near-termwith new technologiesand developing next-generation technologies – and investing in renewable energy to power their data centres and networks.

Sustainable design and coding could also help, such asfurther improving video compression. Arecent studyexplored the potential energy and emission reductions of shifting YouTube music videos to audio only when playing in the background.

It is important to keep in mind the scale of emissions from digital technologies compared to other sectors, with digital technologies accounting foraround 1.5% of global carbon emissions.

All sectors and technologiesare needed to help achieve the goals of theParis Agreementand digital technologies are no exception. In fact, digital technologies, such as AI,could help accelerate climate action. But, without sound climate policies, AI could end up just helping tomake oil extraction cheaperorextending the lifetime of coal plants.

What is indisputable is the need to keep a close eye on the explosive growth of Netflix and other digital technologies and services to ensure society is receiving maximum benefits, while minimising the negative consequences – including on electricity use and carbon emissions.

Instead of relying on misleading media coverage, this will require rigorous analysis, corporate leadership, sound policy and informed citizens.

Methodology and sources

The analysis of the carbon intensity of streaming video presented in this piece is based on a range of sources and assumptions, calculated for 2019 or the latest year possible.

- Bitrate:global weighted average calculated based onsubscriptions by countryandaverage country-level data streaming ratesfrom Netflix in 2019;resolution-specific bitratesfrom Netflix. Note: the calculated global weighted average is a slightly conservative assumption, since the country-level bitrate dataexcludes streaming via cellular networks, which typicallyhave lower bitrates.

- Data centres:based on Netflixreported direct and indirect electricity consumption in 2019,number of subscribersas of the end of 2019 and theiraverage viewing habitsand global weighted average bitrate (above). Note: this assumption is also conservative, since the reported Netflix electricity consumption data includes electricity use from studios and offices, which should ideally be excluded when calculating emissions from streaming.

- Data transmission networks:time-based energy intensity values (kWh per hour) based on emerging research fromMalmodin (2020). Weighting of network type is based on Netflixviewing data by devices(95% fixed and 5% mobile). According to Malmodin, data-based energy intensity assumptions (kWh per GB) used previously are not suitable for high bitrate applications, such as streaming video.

- Devices:smartphones and tablets: calculations based onUrban et al. (2014)andUrban et al. (2019), iPhone 11 specifications (power consumptionandbattery capacity), and iPad 10.2specifications; laptops:Urban et al. (2019); televisions:Urban et al. (2019)andPark et al. (2016), and weighted based on Netflixviewing data by devices(70% TVs, 15% laptops, 10% tablets, 5% smartphones). Note: due to a lack of usage data, these assumptions do not include energy use from set-top-boxes and gaming consoles which some TV viewers may be using. As a result, these figures likely slightly underestimate overall device energy use from streaming.

- Carbon intensity of electricity:based on IEAcountry-levelandglobal data, and2030 scenarioprojections.

Update 25/11/2020: This analysis was updated to include new data on viewing hours and new research on the energy use characteristics of data transmission networks at high bitrates, as well as the revised estimate from the Shift Project published in June 2020. The update also adds comparisons to other estimates widely quoted in the media.